Know thy enemy

The markets frustrate OPEC’s efforts to push up oil prices

The cartel is fighting not just shale producers but the futures market

Borrowing three words from Mario Draghi, the central banker who helped save the euro zone, Khalid al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s energy minister, and his Russian counterpart, Alexander Novak, on May 15th promised to do “whatever it takes” to curb the glut in the global oil markets. Ahead of a May 25th meeting of OPEC, the oil producers’ cartel, they promised to extend cuts agreed last year by nine months, to March 2018, pushing oil prices up sharply, to around $50 a barrel. But to make the rally last, a more apt three-word phrase might be: “know thy enemy”. In two and a half years of flip-flopping over how to deal with tumbling oil prices, OPEC has been consistent in one respect. It has underestimated the ability of shale-oil producers in America—its nemesis in the sheikhs-versus-shale battle—to use more efficient financial techniques to weather the storm of lower prices. A lifeline for American producers has been their ability to use capital markets to raise money, and to use futures and options markets to hedge against perilously low prices by selling future production at prices set by these markets. Only recently has the cartel woken up to the effectiveness of this strategy. It is not clear that it has found the solution. The most obvious challenge shale producers have posed to OPEC this decade is the use of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to drill oil quickly and cheaply in places previously thought uneconomic. Once OPEC woke up to this in 2014, it started to flood the world with oil to drive high-cost competitors out of business (damaging its members’ own fortunes to boot). But it overlooked a more subtle change. Fracking is a more predictable business than the old wildcatter model of pouring money into holes in the ground, hoping a gusher will generate a huge pay-off. As John Saucer of Mobius Risk Group, an advisory firm, says, shale has made oil production more like a manufacturing business than a high-rolling commodity one. That has made it easier to secure financing to raise production, enabling producers to spend well in excess of their cashflows. Mr Saucer says the backers of the most efficient shale firms include private-equity and pension-fund investors who demand juicy but reliable returns. They are more likely to hedge production to protect those returns than to gamble on the “home run” of the oil price doubling to $100 a barrel. “Their hedging is very systematic and transparent,” he says. “They don’t mess around with commodity speculation.” Data from America’s Commodity Futures Trading Commission, a regulatory body, bear out the shift. They show that energy and other non-financial firms trade the equivalent of more than 1bn barrels-worth of futures contracts in West Texas Intermediate (WTI), more than double the level of five years ago and representing almost a quarter of the market compared with 16% in 2012. Many of these are hedges, though Mr Saucer says the data only reflect part of the total, excluding bilateral deals with big banks and energy merchants. OPEC and non-OPEC producers unwittingly exacerbated the hedging activity by inflating output late last year even as they decided to cut production from January 1st. The conflicting policies helped depress the spot price relative to the price of WTI futures, preserving an upwardly sloping futures curve known as “contango”. This made it more attractive for shale producers to sell forward their future production, enabling them to raise output.

That higher shale output will persist is borne out by a surge in the number of drilling rigs, which shows no signs of ebbing. The Energy Information Administration, an American government agency, reckons that by next year the United States will be producing 10m barrels of oil a day, above its recent high in April 2015. That would put it on a par with Russia and Saudi Arabia. Shale producers will have gained market share at their expense.

In response, the frustrated interventionists appear now to have set out to put the futures curve into “backwardation”, in which short-term prices are higher than long-term ones. The aim is to discourage the stockpiling of crude, as well as the habit of hedging. But success is not guaranteed.

The International Energy Agency, a forecasting body, said this week that, even if the OPEC/non-OPEC cuts are formally extended on May 25th, more work would need to be done in the second half of this year to cut inventories of crude to their five-year average, which is the stated goal of Messrs al-Falih and Novak. It also noted that Libya and Nigeria, two OPEC members not subject to the cuts because of difficult domestic circumstances, have sharply raised production recently, perhaps undercutting the efforts of their peers.

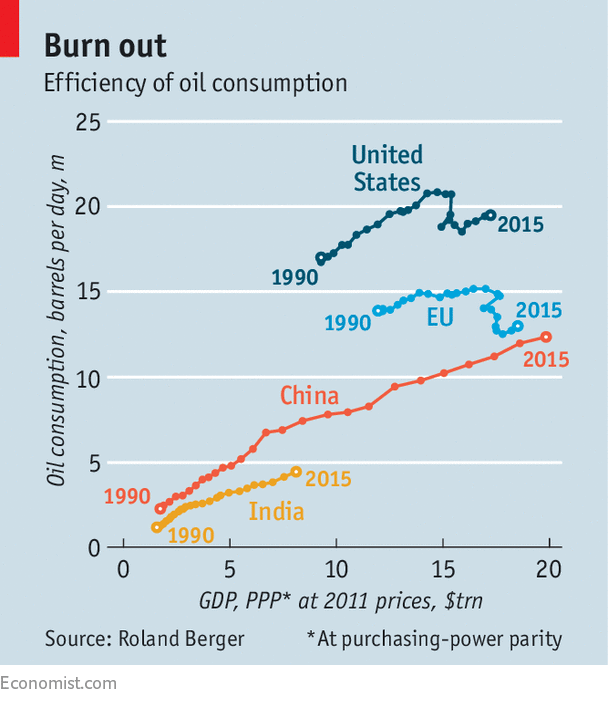

Moreover, global demand this year has been weaker than expected. In a report this week, Roland Berger, a consultancy, argued that rich-country oil demand has peaked, and that, as developing countries such as China and India industrialise, they will use oil more efficiently than did their developed-world counterparts (see chart). All this raises doubts about how far the oil price can climb.

Eventually, shale producers will have their comeuppance. Labour and equipment shortages will push up drilling costs. Higher interest rates will dampen investor enthusiasm. “Irrational exuberance” may lead them to produce so much that prices collapse. But for now, Saudi Arabia seems to be leading OPEC into a war it cannot win. As Pierre Lacaze, of LCMCommodities, a research firm, memorably puts it, it has taken “a knife to a gunfight”. Worse, it has wounded mostly itself.

That higher shale output will persist is borne out by a surge in the number of drilling rigs, which shows no signs of ebbing. The Energy Information Administration, an American government agency, reckons that by next year the United States will be producing 10m barrels of oil a day, above its recent high in April 2015. That would put it on a par with Russia and Saudi Arabia. Shale producers will have gained market share at their expense.

In response, the frustrated interventionists appear now to have set out to put the futures curve into “backwardation”, in which short-term prices are higher than long-term ones. The aim is to discourage the stockpiling of crude, as well as the habit of hedging. But success is not guaranteed.

The International Energy Agency, a forecasting body, said this week that, even if the OPEC/non-OPEC cuts are formally extended on May 25th, more work would need to be done in the second half of this year to cut inventories of crude to their five-year average, which is the stated goal of Messrs al-Falih and Novak. It also noted that Libya and Nigeria, two OPEC members not subject to the cuts because of difficult domestic circumstances, have sharply raised production recently, perhaps undercutting the efforts of their peers.

Moreover, global demand this year has been weaker than expected. In a report this week, Roland Berger, a consultancy, argued that rich-country oil demand has peaked, and that, as developing countries such as China and India industrialise, they will use oil more efficiently than did their developed-world counterparts (see chart). All this raises doubts about how far the oil price can climb.

Eventually, shale producers will have their comeuppance. Labour and equipment shortages will push up drilling costs. Higher interest rates will dampen investor enthusiasm. “Irrational exuberance” may lead them to produce so much that prices collapse. But for now, Saudi Arabia seems to be leading OPEC into a war it cannot win. As Pierre Lacaze, of LCMCommodities, a research firm, memorably puts it, it has taken “a knife to a gunfight”. Worse, it has wounded mostly itself.

Courtesy economist