By Noah Smith

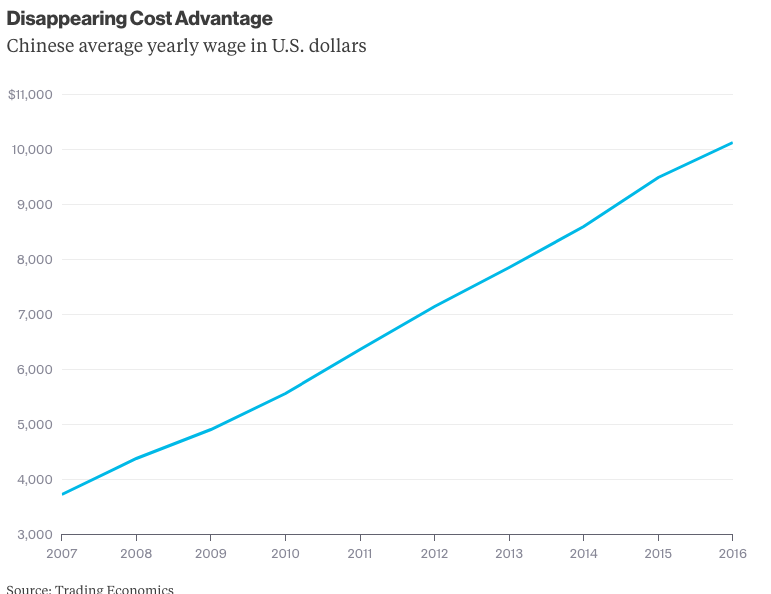

Economists have lately been rethinking free trade. They’re right to do so -- and not just because China’s emergence came as such a big shock to U.S. workers. There used to be a near-universal consensus among academic economists that the best trade policy for any country was to unilaterally remove all barriers and distortions, even if trading partners didn’t do the same. As long as distributional issues could be handled -- by helping people who lost jobs to competition -- free trade was seen as a no-brainer. This cozy consensus has been challenged by analyses of trade with China in the 2000s. During previous episodes of globalization, workers displaced by international competition had found new jobs for similar pay. But when trade was opened up with China, a fifth of humanity -- highly productive workers with very low pay -- suddenly entered the labor market. The speed and extent of the resultant hollowing out of U.S. manufacturing appears to have been too much for many workers, who tended to get stuck in lower-paying jobs or on the welfare rolls. Economists thus realized that there was a big problem with free trade that the classical theory hadn’t prepared them for: the difficulty of adjusting to huge and sudden changes in the trading system. This should make them consider other ways that the simple Econ 101 theory might not be the whole story. During a recent discussion on the Andreessen Horowitz podcast, I laid out another reason free trade could go awry. There’s a theory that cheap labor causes businesses to skimp on investment in labor-saving technology. When there are a whole lot of low-wage workers around, why invest in developing expensive automation or industrial robots, especially if your competitors are just going to copy your innovation eventually? Substituting cheap human hands for expensive research and development can boost profits in the short term, but in the long term it may lead to less innovation. If this theory is right, then the China trade boom of the 2000s might have delayed the push for automation, and thus slowed down productivity growth. In the short term, a surge of cheap human labor looks just like a surge of cheap robot labor, but in the long term, human wages inevitably rise and a lack of innovation undermines further innovation. So some of the slow productivity growth that developed countries are now seeing might be an echo of free trade in the 2000s. But such cases against free trade are limited in two important ways. First of all, they ignore the enormous good that free trade did for the previously impoverished people of China. Second, both cases are fundamentally about the past. Thanks to rising wages, the China shock is now over:

Courtesy Bloomberg